As a child of the late 1980s, the Nintendo 64 was the first console that I really grew up with. Sure, we had an SNES in the house, but I wasn’t old enough to play without asking my dad to beat the hard levels until I bought an N64 in 1996.

And what a legendary console it was. Super Mario 64, Banjo Kazooie, Goldeneye 007, Super Smash Bros., Ocarina of Time, and Majora’s Mask — so many classic titles that remain a core memory of my childhood.

When I went to revisit my favorite games more than two decades later, my nostalgia goggles were absolutely shattered. The controller is even more dogshit than I remembered, and to make matters worse, N64 emulator performance paled in comparison to other retro platforms.

I mostly gave up on N64 emulation until a few weeks ago when I heard about the fully native PC Majora’s Mask port. That sent me down a deep decomp rabbit hole that has me very excited for the future of retro gaming on all platforms, including Android.

Decomp, recomp, goomba stomp

Robert Triggs / Android Authority

N64 emulators have existed for more than 20 years at this point, but there’s a huge difference between emulation and decompilation. Essentially, decompilation projects take the original machine code from the game and then attempt to reverse-engineer code that compiles into the same thing. The result is human-readable code that can be tweaked to improve or modify games on modern hardware.

Decomps have been around for a very long time, but for more difficult platforms like the N64, it typically takes several years for a single game to be decompiled. However, the results are heads and tails above anything an emulator can produce. For example, Super Mario 64 was fully decompiled in 2020, leading to support for widescreen output, improved framerates, and even ray tracing on the nearly 28-year-old game.

For reference, Super Mario 64 originally ran at 320 x 240 and ranged from 20 to 30 fps. The 44mm version of the Apple Watch has a resolution of 368 x 448, and it’s physically smaller than the Nintendo 64 Expansion Pak, which contained a whopping 4MB of RAM. (Doubling what the console shipped with!)

Nintendo 64 ports can now be generated in a matter of seconds.

These efforts have also enabled absolute mad lads like Kaze Emanuar to optimize the source code to run much better on the original hardware. By picking through the code line-by-line, Kaze improved render speeds significantly, leading to a 50% increased framerate. Those results were from two years ago, so it’s possible it’s been optimized even further.

Again, this process typically takes years and a lot of expertise, but the resulting code can then be ported to other platforms by other developers. That’s what happened with the Majora’s Mask port I mentioned above. Each developer’s effort builds on others’ efforts, resulting in a robust library of mods and other assets.

Mishaal Rahman / Android Authority

Now, a process called static recompilation has the potential to speed that up to a few days or weeks.

Static recompilers essentially automate the process of reverse-engineering a ROM’s code, turning a long and laborious task into one that finishes in literally seconds. Importantly, the result is also compiled, so there isn’t any source code to tweak. Still, the results can typically be played right out of the box, which is an incredible achievement.

Just last month a developer with the monicker Wiseguy announced that they had used a static recompiler to create a playable version of Majora’s Mask in just two days. The native PC port supports most, but not all, of the same modern features as the decompilation, opening the floodgates for more speedy ports.

At this point, Wiseguy expects the process to work for nearly the entire N64 library and already has working ports for many games. Even Superman 64 has a port if you want to relive one of the worst games ever made.

Skirting the Hyrule of law

Nick Fernandez / Android Authority

You might think that Nintendo’s lawyers are chain-chomping at the bit to shut these projects down. After all, the company effectively wiped out Yuzu (and Citra) earlier this year without even proving anything in court.

But decomp and recomp projects are not so simple. Rather than release the results as a playable ROM, developers release an executable that requires an original ROM. Essentially, the text, sprites, textures, and other assets are pulled from the ROM, but the rest of the code is entirely new, so Nintendo theoretically doesn’t own it.

Most of these projects also focus exclusively on the decomp/recomp process, and don’t develop any working ports themselves. The Android port of Majora’s Mask, for example, is a port of a port of the original decompilation project.

Nintendo has much less legal standing when it comes to decompilation projects.

In some ways, it’s more similar to the Analogue Pocket or Epilogue GB Operator, allowing you to play your existing games on different hardware. Nintendo certainly isn’t making more Nintendo 64 consoles, so without this, my entire collection of physical cartridges might as well go straight into a dump.

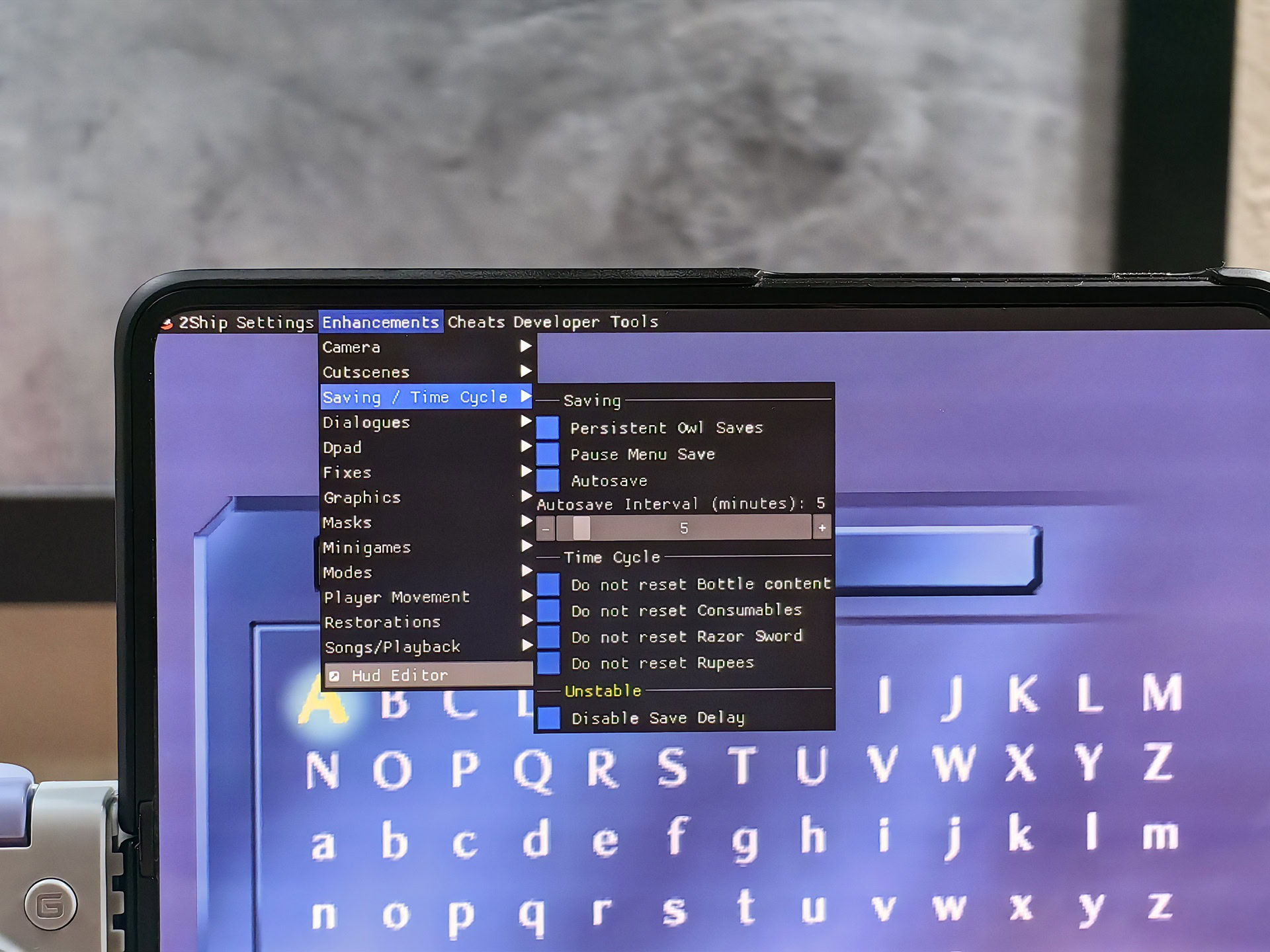

There may be some IP issues, but as far as I can tell, all of these projects are helmed by enthusiasts and don’t generate revenue. A big goal of decomp/recomp projects is to preserve the games we love, since emulators can only achieve so much. Nintendo might want you to pay $50 a year for the Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack that includes some N64 titles and another $50 for a Switch-compatible N64 controller, but that’s still just an emulator without any options to customize the experience.

If we want retro games to thrive, we need more native ports. Playing Majora’s Mask with a Razer Kishi on my phone at 60fps in resolutions I couldn’t have dreamed of in the 1990s has rekindled my love of gaming in a way this thirty-something father of two no longer thought was possible.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·